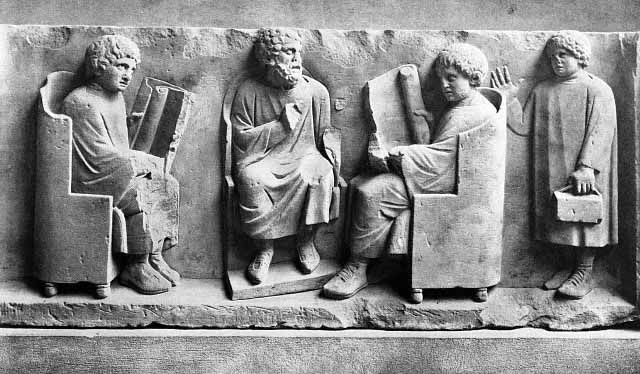

In Why Christianity Happened (Westminster, 2006), New Testament scholar James G. Crossley adds an intriguing reason for the rise of Christianity to the usual set of factors. It is widely understood that the Roman Empire created a set of conditions conducive to the expansion of the Christian religion, such things as relatively rapid communications and an era of peace and stability. Church historians also point to the person of Christ himself and the quality of church life as factors in that growth. To this list, Crossley adds another factor, which was that an increasing number of citizens of the Empire were attracted to monotheism as a theological choice. Judaism had something to do with the spread of monotheism, but there were also pagan versions as well. Thus, when the Jesus Movement cut loose from Judaism and the cultural restraints it placed on converts, there was a ready pool of people primed in a sense to receive this new religious movement (see pages 99-101).

Like a depressingly large number of "facts" when it comes to the history of the Jesus Movement/church in biblical times, this is a matter of speculation although Crossley makes a good case for the argument that monotheism was an attractive, cutting edge theology at the time. IF he is correct, it suggests that the Jesus Movement took hold because of its congruence with the spiritual temper of its times, not because it stood over against that temper. It spoke to the spiritual aspirations of at least one key segment of Roman society in spite of the political opposition it provoked.

It only makes sense that any viable religious faith must speak to the spiritual and theological sensibilities of an important part of society in its time and place. In our time, that segment of society to which Christianity speaks most fully seems to be increasingly the more extreme end of conservatism, which embraces dualistic doctrines that are increasingly at odds with the growing secularity and multi-culturalism of international culture. It seems to speak best to that segment of society that represents where we have been spiritually and theologically rather than where we are going. That segment is quite large, so Christianity is in no danger of disappearing any time soon; but it does seem that it has lost a key trait that made it the exciting faith of choice for many in Roman times. It seems to be losing its ability to go with the spiritual flow of our age. As I say, in ancient times the Jesus Movement spoke to where we were going; today Christianity seems to speak best to where we have been.

This is, of course, a matter of speculation, but it is not unreasonable speculation and is worth a good deal of thought.

We should maintain that if an interpretation of any word in any religion leads to disharmony and does not positively further the welfare of the many, then such an interpretation is to be regarded as wrong; that is, against the will of God, or as the working of Satan or Mara.

Buddhadasa Bikkhu, a Thai Buddhist Monk

Sunday, July 14, 2013

Friday, July 12, 2013

Thinking Beyond the Midterm Grade

In an editorial entitled, "Midterm exams," Presbyterian Outlook editor Jack Haberer grades the Presbyterian Church (USA)'s progress nationally between the 2012 and 2014 General Assembly meetings. He gives the denomination a good grade for implementing GA policy and a poor grade for unity. Yesterday, I looked at the grade he gave us for denominational unity, a "C-"; today, I would like to encourage us to think beyond his grading system entirely.

As we saw yesterday, the editorial argues that some of those leaving PC(USA) are doing so in ignorance of the fact that we are not as theologically liberal as they mistakenly think we are. For example, only a little more than one clergy in ten believes other religions can lead to salvation. The editorial apparently faults the whole denomination for not working hard enough to inform the misinformed of the real state of things. Then, the editorial states, "And, while our efforts have been too tepid, too limp, the provocateurs — those who love to play beyond the edges of orthodoxy — use their blog pages and Facebook groups to proclaim their eccentric ideas and pet heresies, thereby reinforcing the negative assessments of the rest of us." The editorial does not elaborate so we are left not quite sure who these "provocateurs" are or where the "edges of orthodoxy" might be. Since the editorial focused on universalism, however, it seems that the "eccentric ideas and pet heresies" being expounded on the fringes of the denomination have to do with that doctrine.

There is, in any event, another way to look at supposedly unorthodox, eccentric, and heretical theological perspectives that is itself less provocative and points to the value of thinking "outside of the box" theologically in a time of rapid change when increasingly large numbers of Americans are rejecting the Christian religion out of hand. Universalism provides an excellent example. Let's start with the simple fact that most American Christians today are functional universalists. Reporting on research conducted in 2008 in a posting entitled, "Many Americans Say Other Faiths Can Lead to Eternal Life," the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life concludes that,

Universalism may still stand beyond the pale of a traditional orthodoxy based on so-called literal readings of the Bible, but one of the running battles we fought as Presbyterians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was over the very issue of traditional orthodoxy. We walked away from the idea that our denomination can or will enforce the twin doctrines of biblical literalism and traditional orthodoxy. We are not literalists, and we encourage a diversity of theological thought.

Given all of this, those bloggers and Face bookers who supposedly stand at the edges of orthodoxy do not seem to be so very far out on the fringe as we might mistakenly think. They, furthermore, have an important role to play, which is to explore new ideas and find culturally relevant ways in which to express our faith. In the Age of Science, it is important that we constantly explore in a positive way the relationship of faith and science. In an age of increasingly secularity, we need to learn how to speak with the "nones" in ways that build bridges rather than walls. In an age of increasing openness to those not like us, we need to learn to be comfortable with diversity. We live in an age that shatters boxes as a matter of course, and it is vital for the sake of the good news that we proclaim to think "outside the box."

Since the Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15), we Christians have demonstrated an aptitude for adapting faith to culture as we seek the redemption of culture. We speak from within the diverse cultures of the world so that we can communicate to them the message of Christ. In a culture bent on change, we must embrace change. We must risk—as previous generations have risked—losing the core of the good news for the sake of speaking about it. To that end, we need a mix of conservatives who are always in danger of not going far enough and liberals who are always in danger of going too far. Each have their place as we try again in our time and place to share what is precious to all of us, conservative and liberal alike. In their day, the abolitionists were widely seen in the church to be provocateurs. In their day, the advocates of the full rights of women in the Presbyterian Church were considered by many to be provocateurs. Those who have argued year after year for the rights of the LGBT community in the church are still considered by many to be provocateurs. Each in their own time disturbed the peace of the church for the sake of the gospel. They were the "reforming" part of "Reformed and always reforming." Now, of course, not all provocateurs are reformers; some are just plain wrongheaded. But, it is important for us to collectively decide over time who speaks for God's justice and who is just talky-talking. It is our task, then, to discern anew the time we live in and how we can in the Spirit speak to and through our time. Amen.

As we saw yesterday, the editorial argues that some of those leaving PC(USA) are doing so in ignorance of the fact that we are not as theologically liberal as they mistakenly think we are. For example, only a little more than one clergy in ten believes other religions can lead to salvation. The editorial apparently faults the whole denomination for not working hard enough to inform the misinformed of the real state of things. Then, the editorial states, "And, while our efforts have been too tepid, too limp, the provocateurs — those who love to play beyond the edges of orthodoxy — use their blog pages and Facebook groups to proclaim their eccentric ideas and pet heresies, thereby reinforcing the negative assessments of the rest of us." The editorial does not elaborate so we are left not quite sure who these "provocateurs" are or where the "edges of orthodoxy" might be. Since the editorial focused on universalism, however, it seems that the "eccentric ideas and pet heresies" being expounded on the fringes of the denomination have to do with that doctrine.

There is, in any event, another way to look at supposedly unorthodox, eccentric, and heretical theological perspectives that is itself less provocative and points to the value of thinking "outside of the box" theologically in a time of rapid change when increasingly large numbers of Americans are rejecting the Christian religion out of hand. Universalism provides an excellent example. Let's start with the simple fact that most American Christians today are functional universalists. Reporting on research conducted in 2008 in a posting entitled, "Many Americans Say Other Faiths Can Lead to Eternal Life," the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life concludes that,

A majority of all American Christians (52%) think that at least some non-Christian faiths can lead to eternal life. Indeed, among Christians who believe many religions can lead to eternal life, 80% name at least one non-Christian faith that can do so. These are among the key findings of a national survey conducted by the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life from July 31-Aug. 10, 2008, among 2,905 adults.If these Pew findings are anywhere near correct, belief in universal salvation seems hardly eccentric. It seems to have become in fact mainstream thinking among Christians. Our Presbyterian "provocateurs," that is, are evidently working on ideas that reflect the thinking of the majority of American Christians, a majority that we can be reasonably sure will only grow with time.

Universalism may still stand beyond the pale of a traditional orthodoxy based on so-called literal readings of the Bible, but one of the running battles we fought as Presbyterians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was over the very issue of traditional orthodoxy. We walked away from the idea that our denomination can or will enforce the twin doctrines of biblical literalism and traditional orthodoxy. We are not literalists, and we encourage a diversity of theological thought.

Given all of this, those bloggers and Face bookers who supposedly stand at the edges of orthodoxy do not seem to be so very far out on the fringe as we might mistakenly think. They, furthermore, have an important role to play, which is to explore new ideas and find culturally relevant ways in which to express our faith. In the Age of Science, it is important that we constantly explore in a positive way the relationship of faith and science. In an age of increasingly secularity, we need to learn how to speak with the "nones" in ways that build bridges rather than walls. In an age of increasing openness to those not like us, we need to learn to be comfortable with diversity. We live in an age that shatters boxes as a matter of course, and it is vital for the sake of the good news that we proclaim to think "outside the box."

Since the Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15), we Christians have demonstrated an aptitude for adapting faith to culture as we seek the redemption of culture. We speak from within the diverse cultures of the world so that we can communicate to them the message of Christ. In a culture bent on change, we must embrace change. We must risk—as previous generations have risked—losing the core of the good news for the sake of speaking about it. To that end, we need a mix of conservatives who are always in danger of not going far enough and liberals who are always in danger of going too far. Each have their place as we try again in our time and place to share what is precious to all of us, conservative and liberal alike. In their day, the abolitionists were widely seen in the church to be provocateurs. In their day, the advocates of the full rights of women in the Presbyterian Church were considered by many to be provocateurs. Those who have argued year after year for the rights of the LGBT community in the church are still considered by many to be provocateurs. Each in their own time disturbed the peace of the church for the sake of the gospel. They were the "reforming" part of "Reformed and always reforming." Now, of course, not all provocateurs are reformers; some are just plain wrongheaded. But, it is important for us to collectively decide over time who speaks for God's justice and who is just talky-talking. It is our task, then, to discern anew the time we live in and how we can in the Spirit speak to and through our time. Amen.

Thursday, July 11, 2013

Rethinking the Midterm Grade

In an editorial entitled, "Midterm exams," Presbyterian Outlook editor Jack Haberer grades the Presbyterian Church (USA)'s progress nationally between the 2012 and 2014 General Assembly meetings. He gives the denomination a good grade for implementing GA policy and a poor grade for unity. His "C-" grade for unity is worth looking at in more detail.

While crediting the denomination for creating over 100 new, alternative worshipping communities in 2012, the editorial devotes much more of its attention to the significant statistical losses of members and churches during the year. The rate of "leakage" was almost staggering even for a denomination that has been declining statistically for decades. In 2012, we saw over 100 churches leave for other denominations and lost over 100,000 members.

The editorial wants to "talk turkey about those losses," but it doesn't. It never mentions who is actually leaving, namely our more conservative/evangelical brothers and sisters, or the reason why they are leaving, which is our collective decision to make room for the ordination of gays and homosexuals. Now, of course, they are not the only ones leaving, but the significant loss of members in 2012 followed hard on the heels of that decision in 2010.

Instead, the editorial blames at least some of this loss on ignorance of the real theological position of the denomination on, of all things, the question of universal salvation. That is, many of those leaving think that the PC(USA) clergy believe that all religions can lead to salvation when only a small minority of 11% actually believe that. The editorial admits that nearly half of our clergy reject the premise that only Christians can be saved and less than half affirm it, but somehow that seems not so bad compared to positively affirming that one can be saved through other religions—somehow. And, supposedly, some of those leaving would stay if they knew the truth of our clergy's real position on universal salvation.

We need to be clear here. In 2010 and 2011, Presbyterian clergy were just as "soft" on the traditional theological doctrine of exclusive salvation in Christ as they were in 2012. Liberals with these beliefs have been around for a long time, but we did not see the sizable exodus in those years that took place in 2012. So many churches left because we changed our ordination standards. Universalism has nothing to do with anything. It may be a contributing factor for some, but if in 2010 the presbyteries had voted against a change in ordination standards most of the churches that have left would still be with us, still fighting to prevent that decision. They lost and they are leaving, and if we are going to "talk turkey" that is the bird we need to hunt.

In terms of the peace and unity of the denomination, then, we should probably give ourselves a slightly higher grade that the editorials' "C-". A year after the 2012 General Assembly we are now a little more unified than we were and likely to find ourselves a bit less conflicted. We may not like the way we are achieving peace and unity through departure rather than reconciliation, but the result is likely to be less distraction with highly controversial issues that do not significantly impact the daily life of our congregations. Maybe we can even begin to devote the bulk of our national attention and energies to planting another 100 new worshipping communities in the coming twelve months and discovering new ways to turn around more of our old worshipping communities. Maybe for the first time in a long, long time we can even moderate the bombast and breast-beating and devote more of our energy to being the church.

While crediting the denomination for creating over 100 new, alternative worshipping communities in 2012, the editorial devotes much more of its attention to the significant statistical losses of members and churches during the year. The rate of "leakage" was almost staggering even for a denomination that has been declining statistically for decades. In 2012, we saw over 100 churches leave for other denominations and lost over 100,000 members.

The editorial wants to "talk turkey about those losses," but it doesn't. It never mentions who is actually leaving, namely our more conservative/evangelical brothers and sisters, or the reason why they are leaving, which is our collective decision to make room for the ordination of gays and homosexuals. Now, of course, they are not the only ones leaving, but the significant loss of members in 2012 followed hard on the heels of that decision in 2010.

Instead, the editorial blames at least some of this loss on ignorance of the real theological position of the denomination on, of all things, the question of universal salvation. That is, many of those leaving think that the PC(USA) clergy believe that all religions can lead to salvation when only a small minority of 11% actually believe that. The editorial admits that nearly half of our clergy reject the premise that only Christians can be saved and less than half affirm it, but somehow that seems not so bad compared to positively affirming that one can be saved through other religions—somehow. And, supposedly, some of those leaving would stay if they knew the truth of our clergy's real position on universal salvation.

We need to be clear here. In 2010 and 2011, Presbyterian clergy were just as "soft" on the traditional theological doctrine of exclusive salvation in Christ as they were in 2012. Liberals with these beliefs have been around for a long time, but we did not see the sizable exodus in those years that took place in 2012. So many churches left because we changed our ordination standards. Universalism has nothing to do with anything. It may be a contributing factor for some, but if in 2010 the presbyteries had voted against a change in ordination standards most of the churches that have left would still be with us, still fighting to prevent that decision. They lost and they are leaving, and if we are going to "talk turkey" that is the bird we need to hunt.

In terms of the peace and unity of the denomination, then, we should probably give ourselves a slightly higher grade that the editorials' "C-". A year after the 2012 General Assembly we are now a little more unified than we were and likely to find ourselves a bit less conflicted. We may not like the way we are achieving peace and unity through departure rather than reconciliation, but the result is likely to be less distraction with highly controversial issues that do not significantly impact the daily life of our congregations. Maybe we can even begin to devote the bulk of our national attention and energies to planting another 100 new worshipping communities in the coming twelve months and discovering new ways to turn around more of our old worshipping communities. Maybe for the first time in a long, long time we can even moderate the bombast and breast-beating and devote more of our energy to being the church.

Wednesday, July 10, 2013

The Evolution of Our Faith

Evolution is not just a biological phenomenon. It is built into us culturally as well. And where we seem to be evolving is away from violence and toward nonviolence, away from injustice and toward justice, and away from discrimination and toward inclusiveness. It is likely that we are still in the early stages of our social and ethical evolution, and its prospects for success are not clear. We may consume our planet and ourselves before the arc of our evolution has a chance to fully kick in and take us back from the brink (or lead us around the brink, or show us how to leap across it). Or it may well be that we evolve toward the Kingdom faster (if only slightly faster) than we destroy ourselves and our world.

Theologically, we can understand evolution as being both a divine test and a manifestation of God's grace. Why we have been created in the way we are is beyond our knowing, at least now. Why we can't just be perfect and skip the massive amounts of pain and suffering that are a part of evolution is also beyond our knowing. It is true that the pain and the beauty of our evolutionary experience are deeply entwined and in their intimate dance lies a truth we keep reaching for and never quite grasp. The Test and the Grace are two sides of the same coin—perhaps dimly like the athlete who must invest hours of dreary sweat and physical pain in pursuing that instance of victorious glory. Or, more powerfully, the reality of both the Test and Grace, that is Cross and Resurrection, are exposed to our view in the person of Jesus Christ.

Theology evolves as well, and a key moment in our Protestant corner of that evolution came with the dawning realization that in spite of certain very clear biblical passages we can, should, and must open the gates of opportunity for full service and authority in the church to women. The battle for racial equality has been of central importance in American society, but it has been the battle for gender equality in the church that has brought us face to face with the need to balance doctrine with justice—actually to tip the scales of faith in the direction of justice over doctrine and the social injustices that sometimes accompany our doctrines. We are learning thus to see the Other who is not our gender, race, ethnicity, political suasion, sexual orientation, or religion as being fully within the shade of God's grace. In this evolutionary direction lies the Kingdom of God's love, justice, and peace. Amen.

Theologically, we can understand evolution as being both a divine test and a manifestation of God's grace. Why we have been created in the way we are is beyond our knowing, at least now. Why we can't just be perfect and skip the massive amounts of pain and suffering that are a part of evolution is also beyond our knowing. It is true that the pain and the beauty of our evolutionary experience are deeply entwined and in their intimate dance lies a truth we keep reaching for and never quite grasp. The Test and the Grace are two sides of the same coin—perhaps dimly like the athlete who must invest hours of dreary sweat and physical pain in pursuing that instance of victorious glory. Or, more powerfully, the reality of both the Test and Grace, that is Cross and Resurrection, are exposed to our view in the person of Jesus Christ.

Theology evolves as well, and a key moment in our Protestant corner of that evolution came with the dawning realization that in spite of certain very clear biblical passages we can, should, and must open the gates of opportunity for full service and authority in the church to women. The battle for racial equality has been of central importance in American society, but it has been the battle for gender equality in the church that has brought us face to face with the need to balance doctrine with justice—actually to tip the scales of faith in the direction of justice over doctrine and the social injustices that sometimes accompany our doctrines. We are learning thus to see the Other who is not our gender, race, ethnicity, political suasion, sexual orientation, or religion as being fully within the shade of God's grace. In this evolutionary direction lies the Kingdom of God's love, justice, and peace. Amen.

Labels:

evolution,

God,

Justice,

Kingdom of God,

Ordination of Women,

Theology

Tuesday, July 9, 2013

The Paths of Trust

Not at every moment of our lives, Heaven knows, but at certain rare moments of greenness and stillness, we are shepherded by the knowledge that though all is far from right with any world you and I know anything about, all is right deep down. All will be right at last. I suspect that is at least part of what "He leadeth me in the paths of righteousness" is all about. It means righteousness not just in the sense of doing right but in the sense of being right—being right with God, trusting the deep-down rightness of the life God has created for us and in us, and riding with trust the way a red-tailed hawk rides the currents of the air in this valley where we live. I suspect that the paths of righteousness he leads us in are more than anything else the paths of trust like that and the kind of life that grows out of that trust. I think that is the shelter he calls us to with a bale in either hand when the wind blows bitter and the shadows are dark.

Frederick Buechner, Listening to Your Life, pp. 179-180

Monday, July 8, 2013

Real Leaders Know When to Give Up

Those who seek to exercise responsible leadership seek to work with others when those others can be worked with. Working with others requires a certain level of trust, however modest. Working with others requires a certain level of willingness to be worked with. Blame for dysfunctional relationships is not necessarily symmetrical as can be testified to by large numbers of abused spouses and children. Leaders do not have control over many of the factors that limit their effectiveness, including whether or not other leaders are willing to work with them. In our current political climate, there is a set of influential individuals for whom the very idea of compromise is anathema. They will not be worked with, and it is their fault that they will not compromise even for a greater good—if fault is to be found.

"Real leaders" thus accept responsibility for their own actions and the degree to which they make a full-faith effort to work with others. They do not own a dysfunctional relationship they tried to make work to the best of their ability. "Real leaders" also understand that there are others with whom they should not work under any circumstances. One of the things an ethical leader has to learn is who can be worked with and who cannot, who can be trusted and who cannot. An effective leader, in sum, won't buy into absolute, dogmatic statements about "real leaders." As with most things in life, effective leadership is complicated and requires wisdom rather than axioms. Rainer's axiom concerning "real leaders" assumes that such leaders are always in control of the situations they face, and that is seldom true.

Dr. Rainer's statement should thus be modified to read, "Effective leaders find ways either to work with or, if necessary, work around others. Effective leaders accept responsibility for their own actions in light of the real world situations they face. Finger pointing is another issue entirely."

Sunday, July 7, 2013

Wisdom of Lake & Forest

In the drifting quiet of a North Woods morning, nature herself seems to speak. Whatever humanity does or fails to do, however destructive its presence seems to be, life will prevail. If diversity is being lost, it will be regained. If climate change is rapid, its effects increasing, this is just another era, another phase. Life is fragile and resilient. And there are still places of silence where the natural wisdom planted deep in our souls is nourished and coaxed to the surface. This is not the end. It is just another beginning, things are always beginning, even in pain and bloodshed and in the rumors of crises things are always new, always beginning.

If cultures are dying, culture is alive and as vibrant as ever. Right here in the North is a culture built out of longer winters, shorter summers...built out of migrant peoples...with its own words, its own ways. It is sad, yes, to lose languages at the rate of a hundred or more a year, but language itself lives on, thriving in us as it always has since we first learned to speak.

One wonders, drifting quietly on the lake in the midst of the forest, one wonders what it is all of our heedless destruction of the old worlds and words of the past is building for the future. Birth requires pain. Is that what is going on? Or are we crafting a painful death for ourselves and an end to our human version of wisdom? The lake says, life goes on. The forest says, ends are beginnings too.

If cultures are dying, culture is alive and as vibrant as ever. Right here in the North is a culture built out of longer winters, shorter summers...built out of migrant peoples...with its own words, its own ways. It is sad, yes, to lose languages at the rate of a hundred or more a year, but language itself lives on, thriving in us as it always has since we first learned to speak.

One wonders, drifting quietly on the lake in the midst of the forest, one wonders what it is all of our heedless destruction of the old worlds and words of the past is building for the future. Birth requires pain. Is that what is going on? Or are we crafting a painful death for ourselves and an end to our human version of wisdom? The lake says, life goes on. The forest says, ends are beginnings too.

Friday, July 5, 2013

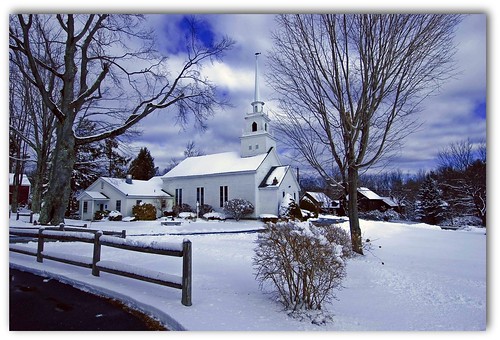

Measuring Successful Pastorates

Measuring successful pastorates these days is a tricky business. A successful pastorate is measured not only by what happens during the years that a pastor serves the church. It depends also on what happens after the pastor leaves. There is a class of pastors who are apparently successful during the years they serve, but they build that "success" on their own personality. The next pastor is left with a challenge that only a few successors can meet, namely picking up where their charismatic predecessor left off. Eventually, the chain of charismatic pastors will break, and the church will go into decline. Even a relatively competent pastor finds it very difficult to follow a pastor who has built her success on her own personality.

It is the churches that suffer. A charismatic pastor attracts people who are "there" for the pastor, not for the church, and often these folks become leaders in the church. Once their "beloved pastor" leaves, these folks lose interest very quickly. They may wait around to see what the next pastor is like, but they are seldom satisfied with the successor to their idol. And they bail, usually quietly, sometimes noisily. The successor and the church are left holding the bag. The church is weakened.

Now, "back in the day" churches could go through periods of boom and bust without incurring permanent damage. That is no longer the case, at least for mainline churches. Today, it takes only one failed pastorate to send a church into a permanent tailspin. In our more complex age, an apparently successful pastorate built on the personality of the pastor is dangerous to the health and future of the church such a pastor serves. All of the excitement and growth is but a prelude to decline, sometimes even disaster. The longer the charismatic pastor serves, the more dangerous his pastorate is to the future of the church.

A successful pastor today is one who leaves the church she serves stronger. It's members are committed to the church, not the pastor. They have been given the space to exercise significant leadership for themselves. People are attracted to the church because of the quality of its life, not the charisma of its pastor. Dollars will get you donuts the church has a good number of active small groups, which take responsibility for themselves as a matter of course. Today's truly successful pastor leaves a congregation built on the strengths of the congregation, which over the years have been cultivated and enhanced. The church is charismatic, rather than the pastor. The Spirit, that is, works through the medium of the whole church, not just the personality of the pastor. A charismatic mainline church has every opportunity to grow, depending of course on its locale because it will in and of itself be attractive to others. Pastors who work with their churches to the end that the church will be charismatic are ones who are more likely to have successful pastorates because when they leave the church has the strength and commitment to carry on.

Measuring successful pastorates these days is a tricky business.

It is the churches that suffer. A charismatic pastor attracts people who are "there" for the pastor, not for the church, and often these folks become leaders in the church. Once their "beloved pastor" leaves, these folks lose interest very quickly. They may wait around to see what the next pastor is like, but they are seldom satisfied with the successor to their idol. And they bail, usually quietly, sometimes noisily. The successor and the church are left holding the bag. The church is weakened.

Now, "back in the day" churches could go through periods of boom and bust without incurring permanent damage. That is no longer the case, at least for mainline churches. Today, it takes only one failed pastorate to send a church into a permanent tailspin. In our more complex age, an apparently successful pastorate built on the personality of the pastor is dangerous to the health and future of the church such a pastor serves. All of the excitement and growth is but a prelude to decline, sometimes even disaster. The longer the charismatic pastor serves, the more dangerous his pastorate is to the future of the church.

A successful pastor today is one who leaves the church she serves stronger. It's members are committed to the church, not the pastor. They have been given the space to exercise significant leadership for themselves. People are attracted to the church because of the quality of its life, not the charisma of its pastor. Dollars will get you donuts the church has a good number of active small groups, which take responsibility for themselves as a matter of course. Today's truly successful pastor leaves a congregation built on the strengths of the congregation, which over the years have been cultivated and enhanced. The church is charismatic, rather than the pastor. The Spirit, that is, works through the medium of the whole church, not just the personality of the pastor. A charismatic mainline church has every opportunity to grow, depending of course on its locale because it will in and of itself be attractive to others. Pastors who work with their churches to the end that the church will be charismatic are ones who are more likely to have successful pastorates because when they leave the church has the strength and commitment to carry on.

Measuring successful pastorates these days is a tricky business.

Tuesday, July 2, 2013

Telling the Truth About War

James Holland, The Battle of Britain (St. Martin's, 2010), poses a serious question concerning how we view war generally. Drawing mostly on personal stories of those involved, especially pilots from both sides, Holland renders an almost intimate portrait of the Battle of Britain, which celebrates the courage of the pilots and the role the British played in turning the tide against Nazi Germany. The larger elements of strategy and tactics and the ways and means of the war are included, but in a less prominent role than usual. The book is about the people that fight wars as much as it is about war itself.

War is not good, the lesson seems to be, but there are things related to war that can be taken to be good. Pilots were courageous, Britons and Germans sacrificial, and Britain's staying power and superior skills at waging modern war praiseworthy. That's fine as far as it goes, but what do we do with it? Do courage, heroism, grit, and fortitude tip the balance sheet of war, if even slightly? Or, do they serve to highlight the evil of war by their contrasting goodness? Is war itself a mixed bag of good and evil? Or is it unmitigated evil to which people respond with good qualities? For my money, it is the latter. The human spirit does find ways to turn even the most evil aspects of human nature to a good that is not inherent in the evil. We can create good out of the evil, just as we seem endlessly able to subvert good to evil ends.

Perhaps it is not necessary to come away from every book about war with a feeling of revulsion for the institution itself, but perhaps we should remain at least somewhat conscious of what lies behind the courage and heroism—the backdrop of war. That is what I personally found understated in Holland's portrait of the Battle of Britain, the backdrop of pain and misery the whole world suffered because of World War II. It is there, for example, in the deaths of individual pilots, but understated nonetheless. Pain, death, suffering, and destruction are the main themes of any history of war, and where they are not sufficiently present in the historian's prose her or his history is less than adequate. It is less than an accurate historical portrayal of war.

War is not good, the lesson seems to be, but there are things related to war that can be taken to be good. Pilots were courageous, Britons and Germans sacrificial, and Britain's staying power and superior skills at waging modern war praiseworthy. That's fine as far as it goes, but what do we do with it? Do courage, heroism, grit, and fortitude tip the balance sheet of war, if even slightly? Or, do they serve to highlight the evil of war by their contrasting goodness? Is war itself a mixed bag of good and evil? Or is it unmitigated evil to which people respond with good qualities? For my money, it is the latter. The human spirit does find ways to turn even the most evil aspects of human nature to a good that is not inherent in the evil. We can create good out of the evil, just as we seem endlessly able to subvert good to evil ends.

Perhaps it is not necessary to come away from every book about war with a feeling of revulsion for the institution itself, but perhaps we should remain at least somewhat conscious of what lies behind the courage and heroism—the backdrop of war. That is what I personally found understated in Holland's portrait of the Battle of Britain, the backdrop of pain and misery the whole world suffered because of World War II. It is there, for example, in the deaths of individual pilots, but understated nonetheless. Pain, death, suffering, and destruction are the main themes of any history of war, and where they are not sufficiently present in the historian's prose her or his history is less than adequate. It is less than an accurate historical portrayal of war.

Monday, July 1, 2013

History Lesson

One of the essential lessons of history is that if we use our own categories to describe the past we will seriously misjudge it.

James Hannam, The Genesis of Science (Regnery, 2011)

page xviii

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)