The Public Religion Research Institute has recently released a PRRI/RNS Religion News Survey (here) measuring public support of the Tea Party Movement compared to Occupy Wall Street as well as the public's views on the current state of the American economy. On the one hand, the report reveals a deep, expected divide between Democrats and Republicans concerning the OWS and TPM movements. Republicans, in particular, display significant support for the Tea Party and antipathy towards Occupy Wall Street. On the other hand, a solid majority of Americans are not interested in either movement but do have a real concern for the gap between rich and poor and the state of the economy. This majority, that is, cares about the poor and the economy but is not looking for radical solutions to either problem and support common sense ones instead. They favor raising taxes on the wealthy 1% and making large corporations contribute more. It thus seems only a matter of time until the public wakes up and starts electing moderates from both parties to Congress, sending them to Washington to make common sense compromises aimed at both reducing poverty and the debt. We have to stop sending ideological wackos to Washington. That's a prayer. Amen.

The Public Religion Research Institute has recently released a PRRI/RNS Religion News Survey (here) measuring public support of the Tea Party Movement compared to Occupy Wall Street as well as the public's views on the current state of the American economy. On the one hand, the report reveals a deep, expected divide between Democrats and Republicans concerning the OWS and TPM movements. Republicans, in particular, display significant support for the Tea Party and antipathy towards Occupy Wall Street. On the other hand, a solid majority of Americans are not interested in either movement but do have a real concern for the gap between rich and poor and the state of the economy. This majority, that is, cares about the poor and the economy but is not looking for radical solutions to either problem and support common sense ones instead. They favor raising taxes on the wealthy 1% and making large corporations contribute more. It thus seems only a matter of time until the public wakes up and starts electing moderates from both parties to Congress, sending them to Washington to make common sense compromises aimed at both reducing poverty and the debt. We have to stop sending ideological wackos to Washington. That's a prayer. Amen.

We should maintain that if an interpretation of any word in any religion leads to disharmony and does not positively further the welfare of the many, then such an interpretation is to be regarded as wrong; that is, against the will of God, or as the working of Satan or Mara.

Buddhadasa Bikkhu, a Thai Buddhist Monk

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

OWS, TPM, & Us

The Public Religion Research Institute has recently released a PRRI/RNS Religion News Survey (here) measuring public support of the Tea Party Movement compared to Occupy Wall Street as well as the public's views on the current state of the American economy. On the one hand, the report reveals a deep, expected divide between Democrats and Republicans concerning the OWS and TPM movements. Republicans, in particular, display significant support for the Tea Party and antipathy towards Occupy Wall Street. On the other hand, a solid majority of Americans are not interested in either movement but do have a real concern for the gap between rich and poor and the state of the economy. This majority, that is, cares about the poor and the economy but is not looking for radical solutions to either problem and support common sense ones instead. They favor raising taxes on the wealthy 1% and making large corporations contribute more. It thus seems only a matter of time until the public wakes up and starts electing moderates from both parties to Congress, sending them to Washington to make common sense compromises aimed at both reducing poverty and the debt. We have to stop sending ideological wackos to Washington. That's a prayer. Amen.

The Public Religion Research Institute has recently released a PRRI/RNS Religion News Survey (here) measuring public support of the Tea Party Movement compared to Occupy Wall Street as well as the public's views on the current state of the American economy. On the one hand, the report reveals a deep, expected divide between Democrats and Republicans concerning the OWS and TPM movements. Republicans, in particular, display significant support for the Tea Party and antipathy towards Occupy Wall Street. On the other hand, a solid majority of Americans are not interested in either movement but do have a real concern for the gap between rich and poor and the state of the economy. This majority, that is, cares about the poor and the economy but is not looking for radical solutions to either problem and support common sense ones instead. They favor raising taxes on the wealthy 1% and making large corporations contribute more. It thus seems only a matter of time until the public wakes up and starts electing moderates from both parties to Congress, sending them to Washington to make common sense compromises aimed at both reducing poverty and the debt. We have to stop sending ideological wackos to Washington. That's a prayer. Amen.

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

FPC Log (2) & Isaiah (xi): Resurrection Church

|

| The windmills of Lewis County, NY |

Isaiah's image of a stump is seriously relevant here on the edge of the Adirondacks, a vast semi-wilderness that has seen periods of extensive, destructive logging in days past. Areas heavily logged in the 19th century have since grown back to such an extent that they are once again virtually virgin forest, which regenerated themselves from the seas of stumps left behind by the loggers. Re-growth, renewal, and resurrection are thus natural subjects for a declining mainline church in Lewis County, NY.

It's not like todays congregation at FPC, Lowville, is a stump even metaphorically. Like many (most?) churches in the early-middle stages of its decline, it still exhibits a good deal of healthy life. It can still meet challenges. Worship has its moments of meaning, and the members continue to show care for each other. But, the image of the stump and shoots of new growth is still relevant because it holds the promise of something different that an inevitable decline. There is another church tucked away in the body of the 1950s institutional church, a church that seeks to be reborn as a 21st century church—a resurrection church, if you will. Whether or not it ever emerges into full view remains to be seen, and if it does it will bear some of the marks of its past as it should.

The marks of this 21st century church, if it should emerge, will be a livelier worship life built not on the whims and wishes of its pastor but by the work of the congregation itself. It will inspire a deeper understanding of the Christian life and how that life actually works out in practice. It will be more biblically literate and take pleasure in exploring the rich historical Christian literature that inspires deeper reflection. It will continue to be a church that values openness, acceptance, and diversity, qualities it exhibits today. I suspect that the resurrection church, should we ever see it, will be smaller than now but able to win deeper involvement from more people than it does now because of the quality of its life. More than anything else, this resurrection church will seek to understand the ways in which the Spirit moves in its life and care deeply for living in the Spirit as best it can.

Will it eventually start growing in numbers? I don't know. That's not the issue. The issue is discovering where the shoots are growing and nurturing those shoots, leaving to the Spirit how they grow and trusting that they will grow spiritually.

Monday, November 28, 2011

It Is All About the Stump (x)

This is the tenth in a series of postings looking at the meaning of Isaiah 6 for today; it began (here).

Isaiah 6 closes with a curious analogy. After the Hebrews have been subjected to a brutal process of being repeatedly cut down, only a stump will remain, and "The holy seed is its stump." According to this ancient Hebrew religious text, God's plan was to destroy God's people for their rebellion and immorality, but out of all of that destruction God was going to bring forth new life out of the apparently dead stump.

Read from an early 21st century perspective, this ancient text reflects two important spiritual realities built into us and our world by God. The first is the reality of karma, that is "what goes around comes around." According to the ancient Hebrew myth of the Garden, humanity chose death, and it has been paying the price for that choice ever since. The myth reflects reality. The things we do have consequences for us and for those around us. Individually and collectively we are able to build a more or a less peaceful world by our own peace-making or trouble-making actions. Beat a child and both parent and child pay the price. Hug a child in pain and both the hugger and the hugged reap the benefit. Yes, the innocent suffer, but it is because other human beings make them suffer and suffer themselves (in one way or another) as a consequence. It sounds unjust until one considers that the system ultimately self-selects for justice and peace. Evil choices lead to evil consequences for the chooser. The Arab Spring is only the latest massive human movement clawing its way through the reality of karma toward something better.

According to the ancient Hebrew texts of the Old Testament, the nation and its leaders in their rebellion against God chose injustice and oppression, and they reaped the consequences. Sow death and you get it. This law permeates and defines human reality no more or less than does gravity. Like gravity, it hurts and limits us—and we can't live without it.

Also built into us is the second reality: resurrection. It is a common human experience: we fall and fail, and when the dust settles and we pick up our life again we discover that the "death" of the failure has opened doors to something better than before. It is in resurrection that we experience the grace of God. It is in the rhythms of dying to new life that we feel the work of the Spirit.

And, again, we don't have a clue why things are this way. Anyone who tells you they know God's plan is fooling themselves. What I do believe personally is that God has built a future into us, which in biblical terms we call the Kingdom of God. We are evolving spiritually as much as we are biologically, but to what ultimate end is not clear at all. What is clear is that a Hebrew prophet living 2,800 years ago dimly perceived what we dimly perceive: we reap what we sow, and God the Holy Spirit is constantly at work bringing a new, unexpected thing out of the sowing and reaping—something that transcends and reshapes the fundamental truth of karma. Go figure.

Isaiah 6 closes with a curious analogy. After the Hebrews have been subjected to a brutal process of being repeatedly cut down, only a stump will remain, and "The holy seed is its stump." According to this ancient Hebrew religious text, God's plan was to destroy God's people for their rebellion and immorality, but out of all of that destruction God was going to bring forth new life out of the apparently dead stump.

Read from an early 21st century perspective, this ancient text reflects two important spiritual realities built into us and our world by God. The first is the reality of karma, that is "what goes around comes around." According to the ancient Hebrew myth of the Garden, humanity chose death, and it has been paying the price for that choice ever since. The myth reflects reality. The things we do have consequences for us and for those around us. Individually and collectively we are able to build a more or a less peaceful world by our own peace-making or trouble-making actions. Beat a child and both parent and child pay the price. Hug a child in pain and both the hugger and the hugged reap the benefit. Yes, the innocent suffer, but it is because other human beings make them suffer and suffer themselves (in one way or another) as a consequence. It sounds unjust until one considers that the system ultimately self-selects for justice and peace. Evil choices lead to evil consequences for the chooser. The Arab Spring is only the latest massive human movement clawing its way through the reality of karma toward something better.

According to the ancient Hebrew texts of the Old Testament, the nation and its leaders in their rebellion against God chose injustice and oppression, and they reaped the consequences. Sow death and you get it. This law permeates and defines human reality no more or less than does gravity. Like gravity, it hurts and limits us—and we can't live without it.

Also built into us is the second reality: resurrection. It is a common human experience: we fall and fail, and when the dust settles and we pick up our life again we discover that the "death" of the failure has opened doors to something better than before. It is in resurrection that we experience the grace of God. It is in the rhythms of dying to new life that we feel the work of the Spirit.

And, again, we don't have a clue why things are this way. Anyone who tells you they know God's plan is fooling themselves. What I do believe personally is that God has built a future into us, which in biblical terms we call the Kingdom of God. We are evolving spiritually as much as we are biologically, but to what ultimate end is not clear at all. What is clear is that a Hebrew prophet living 2,800 years ago dimly perceived what we dimly perceive: we reap what we sow, and God the Holy Spirit is constantly at work bringing a new, unexpected thing out of the sowing and reaping—something that transcends and reshapes the fundamental truth of karma. Go figure.

Sunday, November 27, 2011

The God Who is Not Love (ix)

This is the ninth in a series of postings looking at the meaning of Isaiah 6 for today; it began (here).

It is chapters like Isaiah 6 that give the God of the Old Testament a bad name and a somewhat sinister reputation among the masses. In popular imagination, the OT God is jealous, angry, into judgment big time, wipes out whole cities, drowns armies, and all-in-all a rather nasty fellow. On the other hand, God seldom gets credit for being slow to anger and quick to forgive, and the OT God's long-suffering patience with the Hebrew people is pretty much overlooked. God's act of freeing the Hebrews from slavery and his special concern for widows and orphans (social marginals) is ignored. The deep affection the psalmist who penned Psalm 23 had for God doesn't matter apparently.

So, what do we do with a passage like Isaiah 6:9-11 where God tells the prophet to preach a message that won't be heard so the people's minds will be dulled and their senses distorted so they won't turn to God (repent) and be healed? God tells Isaiah to keep up this kind of preaching until Judah's cities are emptied and the whole nation including its land is laid waste. In other words, God intends nothing less than genocide of such proportions that even the land will become barren.

This is hard stuff, however we try to explain it. I'm not sure there is any explanation that will satisfy early 21st century readers (other than the biblical literalists) because what we're dealing with here is a view of reality crafted 2,800 years ago in a world that valued violence differently than we do now. Still, a case can be made that relative to the spiritual landscape of the age, YHWH (the God of the Hebrews) was a markedly beneficent and loving deity that did not demand child sacrifice but did command justice and called on his people to love him rather than fear him. Other gods had little concern for the poor. Other gods had to be bought off with offerings and rite and rituals, while this God said repeatedly through the prophets that such things are useless when there is no justice. Hence the prophet Micah's message that all God demands of his people is that they act justly, love kindness, and walk in humility with God (Micah 6:8).

Nonetheless, the authors of the Old Testament worshipped a God who had a violent, genocidal side. We have to accept that and insist again that not everything in the Bible is Christ-like or worthy of our faith. We put our ultimate faith in Christ not the Bible, which means we can critically reject negative aspects of the Bible while still accepting its authority under Christ and in light of Christ. Christ constrains scripture. Scripture does not constrain Christ.

But, we haven't gotten to the stump yet. Once again, stay tuned.

It is chapters like Isaiah 6 that give the God of the Old Testament a bad name and a somewhat sinister reputation among the masses. In popular imagination, the OT God is jealous, angry, into judgment big time, wipes out whole cities, drowns armies, and all-in-all a rather nasty fellow. On the other hand, God seldom gets credit for being slow to anger and quick to forgive, and the OT God's long-suffering patience with the Hebrew people is pretty much overlooked. God's act of freeing the Hebrews from slavery and his special concern for widows and orphans (social marginals) is ignored. The deep affection the psalmist who penned Psalm 23 had for God doesn't matter apparently.

So, what do we do with a passage like Isaiah 6:9-11 where God tells the prophet to preach a message that won't be heard so the people's minds will be dulled and their senses distorted so they won't turn to God (repent) and be healed? God tells Isaiah to keep up this kind of preaching until Judah's cities are emptied and the whole nation including its land is laid waste. In other words, God intends nothing less than genocide of such proportions that even the land will become barren.

This is hard stuff, however we try to explain it. I'm not sure there is any explanation that will satisfy early 21st century readers (other than the biblical literalists) because what we're dealing with here is a view of reality crafted 2,800 years ago in a world that valued violence differently than we do now. Still, a case can be made that relative to the spiritual landscape of the age, YHWH (the God of the Hebrews) was a markedly beneficent and loving deity that did not demand child sacrifice but did command justice and called on his people to love him rather than fear him. Other gods had little concern for the poor. Other gods had to be bought off with offerings and rite and rituals, while this God said repeatedly through the prophets that such things are useless when there is no justice. Hence the prophet Micah's message that all God demands of his people is that they act justly, love kindness, and walk in humility with God (Micah 6:8).

Nonetheless, the authors of the Old Testament worshipped a God who had a violent, genocidal side. We have to accept that and insist again that not everything in the Bible is Christ-like or worthy of our faith. We put our ultimate faith in Christ not the Bible, which means we can critically reject negative aspects of the Bible while still accepting its authority under Christ and in light of Christ. Christ constrains scripture. Scripture does not constrain Christ.

But, we haven't gotten to the stump yet. Once again, stay tuned.

Saturday, November 26, 2011

Send Me (viii)

This is the eighth in a series of postings looking at the meaning of Isaiah 6 for today; it began (here).

The first part of Isaiah 6 is a favorite among preachers, esp. those who want to motivate their congregation in one way or another. It starts with the grand vision, as we've seen, and it ends in verse 8 with God asking, "Who is willing to be my messenger," and Isaiah famously responding, "OK, Lord, I'll go." Unlike other Old Testament figures called by God—Moses and Jeremiah always come to mind—Isaiah didn't hesitate even though God didn't specifically address him with the fateful question. Isaiah, thus, is the epitome of commitment, a wonderful object lesson for all of us—so long as we don't read beyond verse 8. The rest of the chapter is something else again.

Hold that thought while we digress for a moment. Commentators wrestle with the placing of Isaiah's call in chapter 6. Logically, it should be at the very beginning of the book. One theory (a good one so far as I can see) is that the whole call including verses 9 and following only makes sense if the reader understands the actual situation facing the Hebrew people in Isaiah's time. Without going into all the details (see Isaiah 1-5), Isaiah's actual call was to preach doom and gloom, pronounce judgement, and issue dire warnings of a dark future.

In that context, verses 9 and following make more sense. Once Isaiah volunteers to be God's prophet, God basically charges Isaiah to preach a message that will fail to communicate so that the people will not escape the doom that awaits them. When Isaiah asks, "How long am I supposed to preach this message and how long will the people stand under judgment?" God answers, "Until there's nothing left but a stump." The destruction of Judah will be all but total, leaving only a metaphorical stump. Modern-day preachers seldom venture into the hostile territory of verses 9 and following. It is a whole lot less inspiring than what comes before. It's so bad that I can't even end this posting with an "Amen." Stay tuned.

The first part of Isaiah 6 is a favorite among preachers, esp. those who want to motivate their congregation in one way or another. It starts with the grand vision, as we've seen, and it ends in verse 8 with God asking, "Who is willing to be my messenger," and Isaiah famously responding, "OK, Lord, I'll go." Unlike other Old Testament figures called by God—Moses and Jeremiah always come to mind—Isaiah didn't hesitate even though God didn't specifically address him with the fateful question. Isaiah, thus, is the epitome of commitment, a wonderful object lesson for all of us—so long as we don't read beyond verse 8. The rest of the chapter is something else again.

Hold that thought while we digress for a moment. Commentators wrestle with the placing of Isaiah's call in chapter 6. Logically, it should be at the very beginning of the book. One theory (a good one so far as I can see) is that the whole call including verses 9 and following only makes sense if the reader understands the actual situation facing the Hebrew people in Isaiah's time. Without going into all the details (see Isaiah 1-5), Isaiah's actual call was to preach doom and gloom, pronounce judgement, and issue dire warnings of a dark future.

In that context, verses 9 and following make more sense. Once Isaiah volunteers to be God's prophet, God basically charges Isaiah to preach a message that will fail to communicate so that the people will not escape the doom that awaits them. When Isaiah asks, "How long am I supposed to preach this message and how long will the people stand under judgment?" God answers, "Until there's nothing left but a stump." The destruction of Judah will be all but total, leaving only a metaphorical stump. Modern-day preachers seldom venture into the hostile territory of verses 9 and following. It is a whole lot less inspiring than what comes before. It's so bad that I can't even end this posting with an "Amen." Stay tuned.

Friday, November 25, 2011

FPC Log: Ride the Tiger or Die (1)

|

| The windmills of Lewis County, NY |

It is possible, however, that FPC, Lowville, might have a different future than the great majority of those churches. This past Sunday, November 20th, I preached a sermon that described the church's state of decline and its three basic options: OPTION ONE: let the decline be; OPTION TWO: seek to manage the decline wisely; or OPTION THREE: enter a period of discernment seeking to discover how to be a 21st century church—i.e. commit itself to learn how to change dramatically. The congregation has generally greeted the open acknowledgment of its condition with acceptance and even appreciation, and there may be a willingness to embrace the Third Option, a spiritual investigation of how it can become a church of the future rather than the past. Or, maybe not. Like many Presbyterian churches, it has a wealth of leadership ability and an impressive potential (spiritually and organizationally) to be something different than what it is, but that does not mean that it will embrace the challenge of the 21st century. It might—or it might not.

At present roughly 25% of the church's members carry out 75% of the work of the church. Another roughly 24% is somewhat involved and carries most of the remaining 25% of the load. The other 50% of the membership does 1% of the work and mostly goes out of its way to stay uninvolved. These figures may actually be a fair measure of the church's spiritual and institutional life. Like most mainline churches, it is better at being a religious institution (albeit, one still living in the 1950s) than it does at being a faith community. People feel that truth without being able to express it, and most of them don't see the point of getting too involved.

In any event, over the next 12-18 months FPC, Lowville, is going to have to make some fundamental choices about the future. My personal hope is that it will go for Option Three, embrace the challenge, and see where that challenge takes it. I believe that the decline of the mainline church is within the providence of God in ways that I don't really understand. God has built exponentially accelerating change into humanity, and churches either ride the tiger of change or die. As pastor of the church, it is not my place to push or prod the church into any future. My one task is to ask it where it wants to go. If it chooses to embrace decline (as churches mostly do, although seldom self-consciously) then my task as pastor is to help it learn how to manage its declining years wisely. Declining churches can still be vital churches, and Option Two is not a bad option. Even Option One has its positive aspects. But I hope FPC, Lowville, goes for Option Three and enters a time of prayerful, studied spiritual discernment seeking to learn how to be a 21st century church. How cool could that be!

Thursday, November 24, 2011

Point of (Mis)Information

Just so you know, it matters where we get our news from. According to a recent study done at Fairleigh Dickinson University, consumers of some news sources, notably Fox News and (to a lesser extent) MSNBC, are more misinformed about current events than informed. Fox News viewers, in particular, are more likely to believe things are true that are not actually true, for example that TARP was passed by Congress during the Obama Administration when it was actually passed during the Bush presidency. In the case of Fox News, it doesn't matter whether the viewer is a Republican or Democrat. If you watch Fox, chances are you are less well-informed about current events than if you don't watch or listen to or read any news at all. That's scary. And not surprising, either.

Just so you know, it matters where we get our news from. According to a recent study done at Fairleigh Dickinson University, consumers of some news sources, notably Fox News and (to a lesser extent) MSNBC, are more misinformed about current events than informed. Fox News viewers, in particular, are more likely to believe things are true that are not actually true, for example that TARP was passed by Congress during the Obama Administration when it was actually passed during the Bush presidency. In the case of Fox News, it doesn't matter whether the viewer is a Republican or Democrat. If you watch Fox, chances are you are less well-informed about current events than if you don't watch or listen to or read any news at all. That's scary. And not surprising, either.

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Rant Alert: Christmas Carols Are Meant for Singing

There was a time when Presbyterians sang Christmas carols pretty much every Sunday in Advent right up to Christmas Sunday and Christmas Eve. Then, some time in the last 20-30 years it became all the vogue to forgo singing Christmas carols until Christmas Sunday and Christmas Eve. "All the vogue" here means among pastors—not among the laity. Churches wait all year to sing Christmas carols, and it seems almost an act of cruelty to force them to wait, wait, wait until the very end of Advent. People want to sing the carols! And there is such a rich variety of carols that four Sundays in Advent plus Christmas Eve doesn't exhaust the possibilities.

So, Why wait?

So, Why wait?

According to the Liturgical FAQ page of St. Jude's Catholic Church, Ft. Wayne, Indiana, we are to refrain from singing carols,

Then there's the waiting thing. First, we already have a season for reflection and waiting, Lent. Is it really necessary to force churches to go through another one? What more is gained? Second, what does not singing carols have to do with waiting? Yes, of course, the lyrics of the carols celebrate the events of the birth of Christ as recorded in Matthew and Luke, but not as if they are actually happening now. Christmas carols are a reflection of the church's memory of the coming of Christ. We can wait in anticipation of the Coming of Christ while singing them, too. Third, many carols are appropriate for virtually every Sunday of the year. Carols such as "Joy to the World!" and "O Come, All Ye Faithful" voice sentiments not strictly tied to the birth of Christ. Indeed, just as every Sunday is a celebration of the resurrection so, too, every Sunday celebrates the coming of Christ, God with us. Finally, we've already been waiting all year to sing the carols. Enough waiting—let's have some fun!

I suspect this is another post-Vatican II thing where Presbyterian seminaries & preachers got enthusiastic about Catholic liturgical reform and went ye therefore and did likewise—for no good reason, so far as I can tell.

But at the end of the day, all of this is just logic chopping, to a degree. The real reason that churches should sing carols throughout Advent and at other times during the year is because they are fun. They are lively, and many of them invoke fond cultural as well as liturgical memories. In an age of dwindling worship attendance, it is hardly wise to withhold the pleasure of singing carols for the sake of a waiting period that most lay people don't buy into and most aren't even aware of. Jesus, after all, thought of the Kingdom of God as being a party, a banquet that we are invited to, and Christmas carols are a great way to celebrate the party. So, let's sing them to our heart's content! Amen.

So, Why wait?

So, Why wait?According to the Liturgical FAQ page of St. Jude's Catholic Church, Ft. Wayne, Indiana, we are to refrain from singing carols,

"For the same reason we don’t sing “Jesus Christ Is Risen Today, Alleluia!” during Lent. We are waiting. We are preparing. We are getting ready for the feast. It is not yet time to shout and celebrate. That time will come, and we’ll be ready for it. During Advent, we dwell with the prophets of old who yearned for God’s coming. Though, of course, Emmanuel is already with us, we take the time to reflect on what it means to wait for the fullness of God’s coming. The kingdom of God is among us – but not yet fully realized. That’s up to us. So now we consider the whats, hows and whos of our participation in the coming of God’s reign on earth. We wait for Jesus coming in history. We wait for Jesus coming to us as we assemble and pray. We wait for Jesus coming to us in the proclamation of the scriptures. We wait for Jesus coming to us in Holy Communion and all the sacraments. We wait for Jesus coming for each of us at the end of our lives. We wait for Jesus coming in glory at the end of time. After more than three weeks of quiet, reflective waiting, we are ready to shout: “Joy to the world! O come, all ye faithful! Hark, the herald angels sing!” But until then, we anticipate with delight what we know will come on December 24, in the middle of that Silent Night, Holy Night."Yes, OK, but...seriously? For starters, there is no reason why churches can't sing "Jesus Christ is Risen Today, Alleluia" on any given Sunday. Every Sunday is a celebration of the resurrection, which is why we worship on Sundays to begin with. The only reason we don't sing so-called Easter hymns on other Sundays is because we don't—that's all. We could. We should. But, through force of habit we don't.

Then there's the waiting thing. First, we already have a season for reflection and waiting, Lent. Is it really necessary to force churches to go through another one? What more is gained? Second, what does not singing carols have to do with waiting? Yes, of course, the lyrics of the carols celebrate the events of the birth of Christ as recorded in Matthew and Luke, but not as if they are actually happening now. Christmas carols are a reflection of the church's memory of the coming of Christ. We can wait in anticipation of the Coming of Christ while singing them, too. Third, many carols are appropriate for virtually every Sunday of the year. Carols such as "Joy to the World!" and "O Come, All Ye Faithful" voice sentiments not strictly tied to the birth of Christ. Indeed, just as every Sunday is a celebration of the resurrection so, too, every Sunday celebrates the coming of Christ, God with us. Finally, we've already been waiting all year to sing the carols. Enough waiting—let's have some fun!

I suspect this is another post-Vatican II thing where Presbyterian seminaries & preachers got enthusiastic about Catholic liturgical reform and went ye therefore and did likewise—for no good reason, so far as I can tell.

But at the end of the day, all of this is just logic chopping, to a degree. The real reason that churches should sing carols throughout Advent and at other times during the year is because they are fun. They are lively, and many of them invoke fond cultural as well as liturgical memories. In an age of dwindling worship attendance, it is hardly wise to withhold the pleasure of singing carols for the sake of a waiting period that most lay people don't buy into and most aren't even aware of. Jesus, after all, thought of the Kingdom of God as being a party, a banquet that we are invited to, and Christmas carols are a great way to celebrate the party. So, let's sing them to our heart's content! Amen.

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

I'm Doomed! (vii)

This is the seventh in a series of postings looking at the meaning of Isaiah 6 for today; it began (here).

This is the seventh in a series of postings looking at the meaning of Isaiah 6 for today; it began (here).In the last couple of postings in this series, we've dwelt on Isaiah's grand vision of God "high and lifted up," and now we come to the flip side—the human side. Isaiah's vision of himself and of his nation was as low as his vision of God was grand. It made him feel small and incredibly unworthy—the creature standing before its Creator. In ancient times, people feared the spiritual powers that they worshipped, and getting too close to those powers was literally life-threatening. Isaiah was a man of his times, and seeing God up close and personal drove him to the depths of fear. And being a man of his times, he thought not just about his own personal unworthiness but also about that of his people. If the lips reveal the true nature of the person and the nation, then he and his people were fearfully unclean. How can the impure stand in the presence of the Pure and Holy One? For Isaiah, he couldn't.

What do we do with this Isaiah's fear today? Should we share it? In colonial and post-colonial America, evangelical Christians certainly did. The most faithful of them constantly, sometimes even frantically took their spiritual temper to see if they had been saved or not. They worried that their relatives, friends, and neighbors had not been saved from hellfire. Preachers thundered from pulpits and people trembled at what they heard. In some circles today, the Christian life is still partly lived in a fear of damnation and hope of a salvation in the face of God's judgment and the prospect of life lived eternally in hell.

For others, we are learning what many learned before us, namely that in Jesus the name of the game has changed. The Creator is not an inimical, angry God casting the faithless into eternal torment. God, rather, is the One who shed the trappings of divinity to be one of us and reveal to us the profound love of God for creation and for us. In Christ, we are learning that compassion is far more powerful than fear. We should still fall on our knees in the presence of God but not in fear so much as in a profound love for the One who first loved us. Amen.

Monday, November 21, 2011

Chain Reaction

Returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that. Hate multiplies hate, violence multiplies violence, and toughness multiplies toughness in a descending spiral of destruction.

So when Jesus says, 'Love your enemies,' he is setting forth a profound and ultimately inescapable admonition. Have we not come to such an impasse in the modern world that we must love our enemies--or else? The chain reaction of evil--hate begetting hate, wars producing more wars--must be broken, or we shall be plunged into the dark abyss of annihilation.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Source: Strength to Love

From Inward/Outward

Sunday, November 20, 2011

Reaching for the Beyond (vi)

This is the sixth in a series of postings looking at the meaning of Isaiah 6 for today; it began (here).

This is the sixth in a series of postings looking at the meaning of Isaiah 6 for today; it began (here).So, Isaiah had this incredible vision described in the first verses of Isaiah 6, which today shoves us to the boundaries of language and or the everyday world. In one way, it was a vision unique to one visionary, a vision the roots of which are now obscured by the passage of time. In another way, however, it is not all that unique. Visionaries have continued to have "peak experiences," as described by the American scholar-psychologist, Abraham Maslow. Pentecostal Christians, for example, experience trance-like states when they speak in tongues. Those who engage in various forms of meditation can have deeply mystical experiences as they meditate. Many individuals experience moments in nature when they feel transported to another plane of peace and joy, however briefly. They may not see visions as clear as Isaiah's, but these experiences can transform their lives, and at the very least give life a deeper sense of purpose and meaning.

Christians generally associate these moments with the Holy Spirit, and we recognize them as a gift of grace. In truth, there are many such Spirit-filled moments if we only have the wit to stop and see them. We stand at the side of the crib of our first-born and feel something that really can't be put into words. That's the Spirit. We sit on a dock in the quiet of the morning listening to birds and feeling the light touch of the breeze, and we feel something that touches us deeply and can't really be expressed in words. That's the Spirit. In our love of another, we sense the Spirit lurking deep below. In the insights we gain from a book or a conversation that are like suddenly seeing something we never saw before, there the Spirit is again. Lurking. Working. Calling us forward and beyond. That is all the work of the Spirit pulling us toward a deeper personal life and a future of peace and harmony that is and will be the Kingdom of God. Amen.

Saturday, November 19, 2011

The Lord, High & Exalted (v)

This is the fifth in a series of postings looking at the meaning of Isaiah 6 for today; it began (here).

This is the fifth in a series of postings looking at the meaning of Isaiah 6 for today; it began (here).God-talk inevitably brings us to the boundaries of what we can do with language. That is certainly the case in the opening verses of Isaiah 6, which recount a vision of God. Some 2,800 years later and translated into English, the tale of that vision has a mystical, spiritual, and exalted quality to it that we cannot miss. Even clothed in the cultural symbols of the ancient world of the Hebrews, we still feel how Isaiah was transported to a higher realm. He saw the King of kings seated on a Throne beyond all thrones and attended by a Court like no other court. The robe of office of this King filled the temple, the Hebrew's most holy spot. In other words, that holiest of holies was filled with the Holiest of holies. God's powerful presence dominated the moment. The temple was also filled with the sounds of overpowering holiness as God's flaming attendants sang praise to God. It was filled with the smoke of holy incense that may have served to obscure the full vision of God so that it did not become entirely overwhelming.

Language is key element of human culture, and it is amazingly useful for daily life. It is a part of our humanity that we cannot do without. But it has its limits, and there are things that we know, feel, and experience that it is all but impossible to put into words. Still, we have to try just as the one who first had this vision, the scribe who first put it to paper, and the editors and translators who have since worked and re-worked the description of the vision—just as all of these individuals have tried to describe Isaiah's vision of God. Lots of people today consider the whole thing nonsense. Many others want to argue about whether it "really happened" or not. They all fail to see the integrity of the vision itself and the way in which it shoves us to the boundaries of language.

The words even now, even translated into English tell the story of an amazing, life-changing experience with the divine. It was a transcendental experience of overwhelming power. It was a moment at once awe-some, awe inspiring, and awe-full. It redefined reality for the visionary.

I'd like to explore the vision further, but again as in the previous posting it is important to stop for a moment and let the vision simply be. It is important to read imaginatively beyond the translation and the ancient cultural images—to peer through them to One beyond—and at least attempt to feel however dimly the power of the vision. Its Otherness. Its Beyond-ness. It takes us to the boundaries of our everyday reality and reminds us that Beyond that reality lies another boundless one—and boundless One. Amen.

Friday, November 18, 2011

The Future of Worship

Back in September, I posted an item entitled "The Future of Entertainment" that reported on the holographic Japanese pop singer, Hatsune Miku. In that posting, I speculated on the possible uses of holographic preachers for worship especially in smaller churches. It would be possible for any church to subscribe to a preaching service that provided excellent holographic preachers each week.

Now, there's more. The American composer and conductor, Eric Whitacre, has created a virtual choir of hundreds of voices all of whom sang one of his pieces individually at home as a home video that Whitacre then combined into a virtual performance. The song is, "Lux Aurumque," a worship piece. You can watch it here:

Those who are interested can check out a brief explanation of how Whitacre put it all together (here).

The point is that members of those small churches I mentioned above could join and sing in a mega-choir that sings incredibly creative music, and they could share that music with the members of their churches. And, I suspect that these virtual options for worship are only the tip of the iceberg for what is possible. Indeed, worship in a decade or five decades may be incredibly different from anything churches have done in worship to in the past. I can't help but wonder, however, how many of today's mainline congregations will be willing to adapt to the coming future in worship—assuming they survive long enough to still be around in that future.

Now, there's more. The American composer and conductor, Eric Whitacre, has created a virtual choir of hundreds of voices all of whom sang one of his pieces individually at home as a home video that Whitacre then combined into a virtual performance. The song is, "Lux Aurumque," a worship piece. You can watch it here:

Those who are interested can check out a brief explanation of how Whitacre put it all together (here).

The point is that members of those small churches I mentioned above could join and sing in a mega-choir that sings incredibly creative music, and they could share that music with the members of their churches. And, I suspect that these virtual options for worship are only the tip of the iceberg for what is possible. Indeed, worship in a decade or five decades may be incredibly different from anything churches have done in worship to in the past. I can't help but wonder, however, how many of today's mainline congregations will be willing to adapt to the coming future in worship—assuming they survive long enough to still be around in that future.

Thursday, November 17, 2011

I Saw the Lord (iv)

This is the fourth in a series of posting looking at the meaning of Isaiah 6 for today; it began (here). In the previous posting in this series (here), we saw that Isaiah's vision is rooted in a particular historical context. In the very first verse of the chapter, however, we are transported to another spiritual plane that transcends the historical context because in the year that King Uzziah died Isaiah saw God. In this sentence, we have crammed together and juxtaposed with each other the two great movements of the Judeo-Christian tradition. Our faith is rooted in the real world we live in, and we ignore our context at our peril. Our faith is rooted in a vision (and experiences) that transcends every context and, in some ways, doesn't even make sense in them. We are constantly standing between here and there, time and eternity, the mundane and the mystical.

This is the fourth in a series of posting looking at the meaning of Isaiah 6 for today; it began (here). In the previous posting in this series (here), we saw that Isaiah's vision is rooted in a particular historical context. In the very first verse of the chapter, however, we are transported to another spiritual plane that transcends the historical context because in the year that King Uzziah died Isaiah saw God. In this sentence, we have crammed together and juxtaposed with each other the two great movements of the Judeo-Christian tradition. Our faith is rooted in the real world we live in, and we ignore our context at our peril. Our faith is rooted in a vision (and experiences) that transcends every context and, in some ways, doesn't even make sense in them. We are constantly standing between here and there, time and eternity, the mundane and the mystical.So, before we go on with our search for insights into Isaiah Chapter 6, we would do well to stop for a moment and remember that ultimately we stand in two places at once and simply cannot explain how or why or what it all means anymore than one can explain snow to someone who has never seen the stuff. Isaiah saw something that cannot be seen. We can't explain it. It is a mystery. For a moment, we do well to stand on the hillside looking out at the inexplicably spectacular sunset with its hues of red, orange, and yellow, and simply let it be.

Isaiah saw God.

Wednesday, November 16, 2011

Ways of Seeing

Occasionally, if I am very fortunate, I place my hand gently on a small tree and feel the happy quiver of a bird in full song.... At times my heart cries out with longing to see these things. If I can get so much pleasure from mere touch, how much more beauty must be revealed by sight.

Yet, those who have eyes apparently see little. The panorama of color and action which fills the world is taken for granted.... It is a great pity that, in the world of light, the gift of sight is used only as a mere convenience rather than as a means of adding fullness to life.

Helen Keller

Source: Three Days to See as quoted in In the Stillness Is the Dancing by Mark Link SJ

From Inward/Outward

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

In the Year King Uzziah Died (iii)

|

| King Uzziah smitten with leprosy |

There are a couple of things that this opening seem to accomplish. First, it roots the vision in the real world of the ancient Hebrew Kingdom of Judah's national and political life. The vision had a real-life context, which mattered. It was a time of political oppression when anyone who cared to look could see all of the things wrong with Judah that Isaiah roundly condemned (see Isaiah 1 - 5) in God's name. So, I need to refine somewhat my contention that it is meaning rather than historicity that matters. It matters that Isaiah's vision has a historical context esp. because the text makes that point itself. An important part of the meaning of the passage is derived from the fact that it is rooted in that context. What isn't so important is all of the debate over who wrote this passage, when it was written, and whether or not it really has anything to do with Isaiah. In any event, we can't grasp the meaning of the whole vision without remembering that Isaiah had it in the midst of seriously troubled, chaotic times.

Second, the footnotes of many versions of the Bible take us to II Chronicles 26, which chapter describes the reign of Uzziah, King of Judah. According to II Chronicles, King Uzziah started out pretty well and was having a successful reign when he let pride get the better of him. In a fit of arrogance, he went to the temple to perform the priestly function of burning incense on the altar, something he did not have the right to do. When reprimanded by the priests and asked to leave, he became angry, and in his moment of anger he contracted leprosy. Then he had to leave and give up his power because he could no longer enter the temple and perform the cultic functions that were required of the king.

The contrast between Uzziah's behavior in the temple and that of Isaiah in his vision is striking. Uzziah behaved arrogantly and even defiantly in the holiest place of the Hebrew people, which for all practical purposes meant he acted this way in the presence of God. In his vision, Isaiah on the other hand was invited into the temple and reacted with humility and a real fear of God's power. The outcome was that he ended up volunteering to become God's prophet. We have then a stark contrast between two power centers, one political and the other prophetic. It is not a contrast between two individuals so much as a window into the failure of Judah's ruling class and its people and the role of the prophet, who speaks for God's different way. That contrast is a dominant theme of the chapter, which is to say the story of Isaiah's vision is a political story pure and simple.

Monday, November 14, 2011

Digging for Meaning in Isaiah 6 (ii & xx)

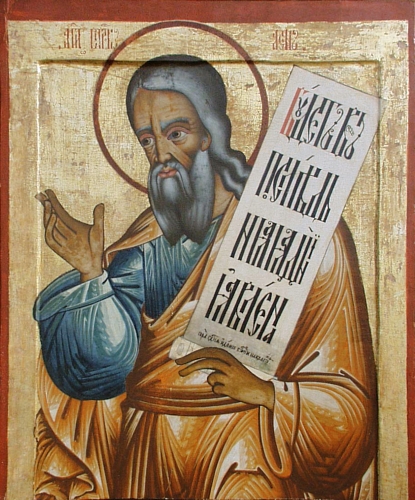

|

| 18th c. Russian icon of Isaiah |

Let me confess that this approach to a biblical story is also rooted in something of an old-fashioned postmodern perspective that proclaims the independence of the reader from the author. Each reader takes over the written document, the "text," and makes of it what she or he will—to a degree. In effect, the reader and the writer enter into a dialogue that is controlled by the reader. It is important to note the complexity of the text as we read it today because it originated about 28 centuries ago and has passed through many hands and several renditions during its journey down the hallway of time to November 2011.

So, what I'm heading into here is a dialogue with the prophet (we'll assume it was Isaiah), the scribe (who wrote down this story), the generations of editors of the Book of Isaiah (who reshaped it into what we have today), and the various translators (who rendered the ancient Hebrew into contemporary English). My task is to treat the story and its long history with respect but not pretend that I can find in it the meanings of the original, which has long been lost and to acknowledge, again, that Isaiah's original audience would have heard the story in different ways even at the very beginning.

What we have in Isaiah 6, in sum, is a story recounting a religious, spiritual, even mystical experience of an individual who claimed that he saw God. I assume that this story began with the 8th century B.C. prophet Isaiah without feeling any need to prove the "fact". It's easier to use his name than to keep saying "the author, whoever he (or she) might be." What was Isaiah's experience, and what can we learn from it for the practice of our faith today? Those are my questions. Put another way, I want to take this story away from the historians, the biblical literalists, and the "non-theist" agitators and recapture a little of the inherent beauty and truth of a story about one man's life-changing encounter with God.

Sunday, November 13, 2011

Isaiah Chapter Six & Us (i)

My sermons at First Presbyterian Church, Lowville, for this week (here) and next week take a look at Isaiah 6, one of the most intriguing chapters in the Bible. In the first part of the chapter, Isaiah is reported to have this weird vision of God high and lifted up in the Temple in Jerusalem. There are seraphim flying around praising God, a booming divine voice, and holy smoke that fills the temple. The chapter starts with the prophet saying, "In the year that King Uzziah died, I saw the Lord...sitting on his throne, high and exalted." (Isaiah 6:1) Isaiah responds to this vision of God by proclaiming his own unworthiness and his feeling that he is doomed, but what actually happens is that God had him cleansed with a hot coal from the altar pressed on his lips and forgave him his sins. Then, God asks, "Who will be my prophet?" Although the question isn't directed specifically to him, Isaiah answers boldly, "I will." (6:8) God's accepts Isaiah's commitment to be a prophet but then commissions him to preach in such a way as to confuse the people of Judah so they won't listen to him and won't be healed. God declares God's intention to destroy the land and send the people off into exile so that only a remnant is left, a stump that will be the beginning of a new future.

My sermons at First Presbyterian Church, Lowville, for this week (here) and next week take a look at Isaiah 6, one of the most intriguing chapters in the Bible. In the first part of the chapter, Isaiah is reported to have this weird vision of God high and lifted up in the Temple in Jerusalem. There are seraphim flying around praising God, a booming divine voice, and holy smoke that fills the temple. The chapter starts with the prophet saying, "In the year that King Uzziah died, I saw the Lord...sitting on his throne, high and exalted." (Isaiah 6:1) Isaiah responds to this vision of God by proclaiming his own unworthiness and his feeling that he is doomed, but what actually happens is that God had him cleansed with a hot coal from the altar pressed on his lips and forgave him his sins. Then, God asks, "Who will be my prophet?" Although the question isn't directed specifically to him, Isaiah answers boldly, "I will." (6:8) God's accepts Isaiah's commitment to be a prophet but then commissions him to preach in such a way as to confuse the people of Judah so they won't listen to him and won't be healed. God declares God's intention to destroy the land and send the people off into exile so that only a remnant is left, a stump that will be the beginning of a new future.I'd like to chew on this chapter for a few postings. There's a lot in the chapter that needs chewing.

For starters, we probably need to talk about the historicity of the passage and get that issue off the table as quickly as we can. Biblical literalists, of course, will insist that Isaiah went to the temple and saw God just as chapter six says he did and get themselves all tangled up in defending the Bible from its attackers (even when no one is attacking). Biblical scholars, on the other hand, will get all tangled up in trying to figure out the historical dimensions of the story. Who really put it in writing? Was Isaiah really involved? What historical period (pre-exilic, exilic, post-exilic) does it really reflect? At the end of the day, scholars don't have clear answers to any of these questions.

What really matters, however, is that this story is filled with meaning. It was meaningful in ancient times, and it remains meaningful today. And what matters is the meaning we can dig out of the story today. It is important to try to understand what it might have meant 2,800 years ago, but we can't know for sure what it did mean then. And we should keep in mind the human fact that different people find different meanings in things like this anyway, whether in ancient times for now. Isaiah's vision didn't mean just one thing then nor does it now. Our focus here, then, is on the meaning of the passage, especially for today. More in the postings that follow.

Saturday, November 12, 2011

Meeting at the Boundaries of Islam & Science

|

| Illustration by an 11th century Islamic scientist of phases of the moon (from Wikipedia) |

In his interview, Prof. Guessoum recalls that Islam has a rich scientific heritage going back a thousand years, which has been largely lost in more recent centuries. Today, science in the Arab nations is dominated by religious concerns and a need to bend science to fit into the mold of religion. He believes that science has declined in the Arab world for three related reasons: dictatorships, corruption, and nepotism & cronyism. Science requires a free environment to thrive, and it has not had that in West Asia and North Africa. The Arab nations, furthermore, see the decline of religion in the West and link that decline in their minds to the influence of science. Even today there are relatively few non-religious academics and those few must maintain a low profile.

Still, Guessoum sees grounds for a dialogue between Islam and the West concerning science, one that would be beneficial to the Arab world because it would foster a more realistic attitude about science and how it is approached. It would teach the Arab world that it cannot simply pick and choose what it wants to believe and not believe regarding scientific findings. It would also inspire greater thought concerning the "proper relationship between faith and reason," an issue of importance in the Muslim world. He believes that the West would benefit as well, esp. since Arab academia has never tried to keep religion "under wraps." If I understand this correctly, Guessoum believes that the Arab world would benefit from an encounter with an independent science that pursues its studies irrespective of religious agendas and the West would benefit from an encounter with a culture that is not as hung up on the relationship of science and religion as we are in Europe and North America.

Guessoum's proposed dialogue between Islam and science offers an intriguing insight into just how important the strategy of dialogue (listening to learn, speaking to share) can be in our conflicted modern world. It also points in a direction that we would do well to consider, namely that religion and science are neither enemies or allies but just two human endeavors that can benefit from each other's views and wisdom in several different ways.

Friday, November 11, 2011

Our Friend (xix)

|

| Our friend |

As a Protestant, there are points at which in find Thich Nhat Hanh's version of Christianity out of focus. I'm rather sure, for example, that his view of faith, which is basically faith in the practice of religion rather than in "notions" of God, is not what I and many other Protestants mean by faith. I find myself not agreeing with some of the parallels he draws between the Holy Spirit and mindfulness. And, as I pointed out in the last posting (xviii) in this series, I definitely disagree of his negative attitudes toward doubt.

Thich Nhat Hanh is however a friend of my (our) faith in at least two ways. First, he pushes at the boundaries of my thinking, causing me to stop, look, and then look again. I don't really accept his call to put away all concepts and notions, but I appreciate his reminder that there is nothing sacred or ultimate in our theologies; and we Christians should spend less time attacking each other because we think differently. Thich Nhat Hanh helps us to see an ugly, unloving side to Protestant Christianity—if only we have the wit to stop, look, and take heed. He also allows me to be playful in my disagreements with his "theology" (or, better, Buddhology), which helps me (us) not take my own theology quite so seriously.

Second, his persistent insistence that practice is the heart of the matter and that religious people of all stripes are prone to deny their faith by their actions is immensely helpful. We (I) need to pay attention when he writes, "In Christianity, as well as in Buddhism, many people have little joy, ease, relaxation, release, or spaciousness of spirit in their practice. Even if they continue for one hundred years that way, they will not touch the living Buddha or the living Christ. If Christian who invoke the name of Jesus are only caught up in the words, they may lose sight of the life and teaching of Jesus. They practice only the form, not the essence." (page 126) While we occasionally cite the Book of James, which instructs us that faith without works is dead, our major concern is often with being on the right side of the hot issues rather than on being loving, kind, joyful, peaceful, patient, and the other fruit and gifts of the Spirit.

At the end of the day, Thich Nhat Hanh gently encourages us to ask the question we don't ask very often if ever, namely what is Christian practice? I suspect that if asked this question most mainline Protestants will answer, "service," and be hard pressed to go much beyond that. We need a friend who will push us to think outside our comfort zone and make us think more seriously about our Christian practice. Thich Nhat Hanh is just such a friend.

Thursday, November 10, 2011

Dualism In One Succinct Sentence

A recent posting in the Huffington Post entitled, "Mississippi 'Personhood' Amendment Vote Fails quoted a supporter of a Mississippi ballot initiative that would have defined life as beginning at the moment of fertilization as saying, "I figure you can't be half for something, so if you're against abortion you should be for this. You've either got to be wholly for something or wholly against it." It would be hard to find a better put or more clearly stated rendition of what is sometimes called "moral dualism" or even "Persian dualism". This form of dualism looks on reality as being divided into two absolute spheres of good and evil, which are in conflict with each other. As a rule, there is no middle ground. If a thing is good then it is good. And if something is evil then it is evil. Rigid boundaries, thus, separate good from evil, right from wrong, and God from Satan. The reigning metaphors of moral dualism are the contrast between black and white and between night and day.

A recent posting in the Huffington Post entitled, "Mississippi 'Personhood' Amendment Vote Fails quoted a supporter of a Mississippi ballot initiative that would have defined life as beginning at the moment of fertilization as saying, "I figure you can't be half for something, so if you're against abortion you should be for this. You've either got to be wholly for something or wholly against it." It would be hard to find a better put or more clearly stated rendition of what is sometimes called "moral dualism" or even "Persian dualism". This form of dualism looks on reality as being divided into two absolute spheres of good and evil, which are in conflict with each other. As a rule, there is no middle ground. If a thing is good then it is good. And if something is evil then it is evil. Rigid boundaries, thus, separate good from evil, right from wrong, and God from Satan. The reigning metaphors of moral dualism are the contrast between black and white and between night and day.The key to it all is that the dual categories, whatever they might be, are absolute. They are separated by a equally absolute boundaries. Thus, by the logic of moral dualism it makes perfect sense to say, "You've either got to be wholly for something or wholly against it." To do otherwise, again by the logic of moral dualism, would be immoral and illogical, it would be a denial of reality. Thus, the more nuanced approach to abortion taken by some, which is both pro-life and pro-choice, is nothing less than dualistic nonsense. "Both...and" simply does not exist in the cognitive landscape of dualism.

The problem with dualism is, of course, that the world we live in and we ourselves are a confusing, inconsistent mixture of things. There is very little in the real world that is black and white. We know this. The sad thing about dualism, thus, is that it forces choices that don't have to be made, creates walls that don't have to be built, and distorts decisions that are better made taking into account the reality of the world we live in. It is a sad fact that all three of the great theist religions—Judaism, Islam, & Christianity—are prone to theological and ideological versions of moral dualism (as are their most vocal critics), which leads said adherents to behave and think in ways that effectively deny the very precepts their faiths teach. There must be a better way, one that for Christians is a more Christ-like way. Amen.

Wednesday, November 9, 2011

Be Careful of the Dragon

Be careful, lest in fighting the dragon you become the dragon.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Source: Unknown

From Inward/Outward

Doubt is Our Friend (xviii)

This is the eighteenth posting in a series of postings reflecting on Thich Nhat Hanh's book, Living Buddha, Living Christ (Riverhead Books, 2007; originally published in 1995). The introductory posting, setting the stage for the series, is (here).

Thich Nhat Hanh does not like doubt. In his view, one goal of the practice of religion is to dispense with what he terms "the abyss of doubt" (page 169). He observes that genuine religious practice leads one to eventually "abandon all ideas and images in order to obtain a truly deep realization." When that realization is achieved, it cannot be taken away from the practitioner because faith in God or nirvana is no longer based on doctrines or notions but on experience (pages 162-163).

Read from a Buddhist perspective, his observations about faith, experience, ideas, and transcending doubt undoubtedly make a good deal of sense so long as we remember that "faith" here means faith in one's practice. It is an empirical "faith," which proves itself trustworthy through repeated testing. Almost like a scientific principle that has been proven through repeated experimentation, the practice of mindfulness through meditation proves itself to such an extent that doubt is no longer possible.

From a Christian perspective, there is a slight problem, which is in the use of the term "faith." If religious practice dispels doubt then it also dispenses with faith. We don't trust in the truth of things that are sure and certain, such as the basic facts of arithmetic. One plus one is two. Period. Full stop. Or, again, that dropped objects fall is not a matter of faith. Let go of an object over thin air, and it will fall. Period. Full stop. If Thich Nhat Hanh is correct that right practice dispels doubt then it does whether we trust it to or not. Or, rather, faith is involved only so long as we are still learning the practice and its trustworthiness in all cases. That is to say that it is not correct to say that mindfulness (or insight) "is the very substance of faith," because it replaces faith with certainty. Where one is sure, one need not trust, and where one does not trust there is no faith.

This is not, I would urge, mere semantics nor is it a criticism of Thich Nhat Hanh. His use of the term "faith" reflects one approach to religion and one description of the goal of religious practice, which is to quench desire and achieve a true, deep, gentle and yet unshakeable peace. Notions of belief, gods, and spiritual forces have nothing to do with the matter—indeed, they must be dispensed with as a part of the process. For Christian, however, we find that we cannot pursue these worthy goals of quenching desire and finding a gut-deep peace apart from our trust, in God in Christ and in God's gift of the Spirit to us. In Buddhism, the self and its desires are quenched. In Christianity, they are offered to God whom we know in the three "masks" of Father, Son, & Holy Spirit. There's not right or wrong here. We're all headed in the same direction. But, we follow differing paths each with their own stunning vistas and dark, muddy swamps.

One key difference between Thich Nhat Hanh's path and one that we can legitimately take as Christians is that for him doubt is an abyss while for us it can be a friend. Amen.

Thich Nhat Hanh does not like doubt. In his view, one goal of the practice of religion is to dispense with what he terms "the abyss of doubt" (page 169). He observes that genuine religious practice leads one to eventually "abandon all ideas and images in order to obtain a truly deep realization." When that realization is achieved, it cannot be taken away from the practitioner because faith in God or nirvana is no longer based on doctrines or notions but on experience (pages 162-163).

Read from a Buddhist perspective, his observations about faith, experience, ideas, and transcending doubt undoubtedly make a good deal of sense so long as we remember that "faith" here means faith in one's practice. It is an empirical "faith," which proves itself trustworthy through repeated testing. Almost like a scientific principle that has been proven through repeated experimentation, the practice of mindfulness through meditation proves itself to such an extent that doubt is no longer possible.

From a Christian perspective, there is a slight problem, which is in the use of the term "faith." If religious practice dispels doubt then it also dispenses with faith. We don't trust in the truth of things that are sure and certain, such as the basic facts of arithmetic. One plus one is two. Period. Full stop. Or, again, that dropped objects fall is not a matter of faith. Let go of an object over thin air, and it will fall. Period. Full stop. If Thich Nhat Hanh is correct that right practice dispels doubt then it does whether we trust it to or not. Or, rather, faith is involved only so long as we are still learning the practice and its trustworthiness in all cases. That is to say that it is not correct to say that mindfulness (or insight) "is the very substance of faith," because it replaces faith with certainty. Where one is sure, one need not trust, and where one does not trust there is no faith.

This is not, I would urge, mere semantics nor is it a criticism of Thich Nhat Hanh. His use of the term "faith" reflects one approach to religion and one description of the goal of religious practice, which is to quench desire and achieve a true, deep, gentle and yet unshakeable peace. Notions of belief, gods, and spiritual forces have nothing to do with the matter—indeed, they must be dispensed with as a part of the process. For Christian, however, we find that we cannot pursue these worthy goals of quenching desire and finding a gut-deep peace apart from our trust, in God in Christ and in God's gift of the Spirit to us. In Buddhism, the self and its desires are quenched. In Christianity, they are offered to God whom we know in the three "masks" of Father, Son, & Holy Spirit. There's not right or wrong here. We're all headed in the same direction. But, we follow differing paths each with their own stunning vistas and dark, muddy swamps.

One key difference between Thich Nhat Hanh's path and one that we can legitimately take as Christians is that for him doubt is an abyss while for us it can be a friend. Amen.

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

Religion & Politics: A Link to A Helpful Posting

E.J. Dionne Jr.'s editorial, "Election 2012’s great religious divide," is worth looking at. In a nutshell, he argues that it's one thing to uphold the separation of church and state and quite another to argue that the religious views of politicians are not fair game for public examination. Check it out.

Jesus Needs Christians

For Christians, the way to make the Holy Spirit truly present in the church is to practice thoroughly what Jesus lived and taught. It is not only true that Christians need Jesus, but Jesus needs Christians also for His energy to continue in this world.

Thich Nhat Hanh,

Living Buddha, Living Christ

page 73

Monday, November 7, 2011

Understanding as the Path to Salvation (xvii)

This is the seventeenth posting in a series of postings reflecting on Thich Nhat Hanh's book, Living Buddha, Living Christ (Riverhead Books, 2007; originally published in 1995). The introductory posting, setting the stage for the series, is (here).

Thich Nhat Hanh believes in understanding. It is for him the path to salvation and the goal of his religious practice. In Chapter Six of Living Buddha, Living Christ (pages 74ff), he argues that understanding brings liberation, compassion, transformation, understanding of others, and forgiveness. He writes, "Buddhist and Christian practice is the same—to make the truth available—the truth about ourselves, the truth about our brothers and sisters, the truth about our situation." Seeking this understanding, he says, "is the most serious work we can do." (page 82) Practice leads to understanding, understanding leads to deep insight into the nature of reality, and insight leads to salvation. And, apparently, salvation leads to better practice and still deeper understanding. The process isn't a straight line thing but rather a downward spiral beyond all categories or notions—toward Nirvana.

The key to it all is right understanding of oneself leading to right understanding of others and reality. Thich Nhat Hanh makes it clear in Living Buddha, Living Christ that the understanding he's talking about here is not mere head knowledge but something much deeper that grows from the experience of meditation. But, it is still understanding.

Christians have long divided themselves into two large camps, those who believe that faith precedes understanding and those who feel that faith proceeds from understanding. It's an old, old debate, and the problem with it is that in the real world faith all too often leads to ignorance rather than understanding; and understanding all too frequently turns into arrogance and sterility. Faith and understanding, belief and practice—these pairs can't be separated from each other. Our faith deepens our understanding while our understanding gives us deeper insights into our faith. They are like partners in an intricate dance where it really does "take two to tango." Amen.

Thich Nhat Hanh believes in understanding. It is for him the path to salvation and the goal of his religious practice. In Chapter Six of Living Buddha, Living Christ (pages 74ff), he argues that understanding brings liberation, compassion, transformation, understanding of others, and forgiveness. He writes, "Buddhist and Christian practice is the same—to make the truth available—the truth about ourselves, the truth about our brothers and sisters, the truth about our situation." Seeking this understanding, he says, "is the most serious work we can do." (page 82) Practice leads to understanding, understanding leads to deep insight into the nature of reality, and insight leads to salvation. And, apparently, salvation leads to better practice and still deeper understanding. The process isn't a straight line thing but rather a downward spiral beyond all categories or notions—toward Nirvana.

The key to it all is right understanding of oneself leading to right understanding of others and reality. Thich Nhat Hanh makes it clear in Living Buddha, Living Christ that the understanding he's talking about here is not mere head knowledge but something much deeper that grows from the experience of meditation. But, it is still understanding.

Christians have long divided themselves into two large camps, those who believe that faith precedes understanding and those who feel that faith proceeds from understanding. It's an old, old debate, and the problem with it is that in the real world faith all too often leads to ignorance rather than understanding; and understanding all too frequently turns into arrogance and sterility. Faith and understanding, belief and practice—these pairs can't be separated from each other. Our faith deepens our understanding while our understanding gives us deeper insights into our faith. They are like partners in an intricate dance where it really does "take two to tango." Amen.

Sunday, November 6, 2011

Reality Check (xvi)

|

| Wat Thai Buddhist Temple, Washington D.C. |

Thich Nhat Hanh has become an important, even inspiring religious figure in Europe and North America. He has published tens of books in English and has quite a "footprint" on the Web. As a representative of Asian Buddhism, thus, he casts quite a long shadow in the West and projects a positive image of his religious heritage that intrigues many "seekers" around the globe. That's good. It can leave, however, an unrealistic appraisal of Buddhism as a very human religion. Like all of the major religions, it is a mixed bag of things that inspire and depress, lift up and undermine. In a recent posting on the Huffington Post entitled, "Western Buddhism: The 50 Year Lessons," the American Buddhist writer, Lewis Richmond, reminds us that the last 50 years have taught Western Buddhists some hard lessons. He lists three: (1) enlightenment is not what Western Buddhists thought it was, and it is something that has to be lived rather than experienced; (2) meditation is not a cure-all, and in some situations it is not helpful at all; and (3) Buddhist books and teachings sometimes obscure the messy, brutal realities of humanity, including Buddhist humanity.