|

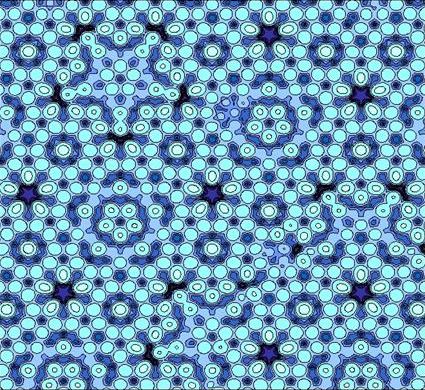

| Atomic model of a silver-aluminum (Ag-Al) quasicrystal (from Wikipedia article) |

Yet, Shechtman knew what he had seen in his electron microscope and persevered in his studies and in his faith in his findings. He has now been more than vindicated with numerous honors and prizes culminating in the Nobel Prize.

In an article in the Israeli newspaper, Al Haaretz, entitled, "Clear as crystal," reporter Asaf Shtull-Trauring quotes Shechtman concerning his tribulations in getting the scientific world to accept his discovery. Shechtman said, "In the forefront of science there is not much difference between religion and science. People harbor beliefs. That's what happens when people believe something religiously. The argument with Linus Pauling was almost theological." More recently, Shechtman himself has written (here), "When I lecture to young students, I always tell them that if they want to be successful scientists who make a contribution, they have to be experts in their fields. But a good scientist also needs faith. I believed in something, and it was hard to break my spirit, despite all the hardships and criticism."

Science is not the cool, rational, objective endeavor the critics of religion would have us believe. It shares traits, both good and not so good, with theology as an academic field and with religion as the pursuit and living out of ultimate truths. A "good scientist" has to bring faith to his or her research and rely on that faith in the pursuit of scientific truth. That's the good. The not so good is that scientists tend to be like other true believers. Once they know 'the Truth," they can be stubborn, willful, arrogant, and ignorant in defending their "truth". Militant anti-theism campaigns against religion because religion is supposedly a public menace. The rhetoric, the anger, and the narrow-minded my-way-or-the-highway attitudes that underlie that campaign suggest that if the day ever comes when militant anti-theism dominates our society, it will prove as dictatorial and oppressive as it thinks religion is.

That is not to say that science and religion are precisely the same. To science's credit, Shechtman has now won over the scientific community because he was right (and because he persevered in being right in the face of strident opposition). In the world of religion, he would have had to start his own denomination. Determining the truth of doctrines is a different ball game, and it takes much longer to resolve things even when they can even be resolved. Still the main point remains. The actual practice of science shows clear parallels with the actual practice of religion. Both are flawed, human practices—a fact the partisans of each practice tend to forget.